To hear the government tell it, its “flagship” Free Senior High School (FSHS) programme has been so successful that it must be protected through legislation before the December 2024 elections to prevent “evil” John Mahama from messing it up if he should return to power in 2025.

At least one government official believes this hype so much that he once boasted that not even Kwame Nkrumah did so much for Ghanaian education, obviously ignorant of the fact that Nkrumah introduced free basic education in 1952, made it compulsory in 1961, and followed it in 1963 with a free secondary education policy under his Seven-Year Development Plan, which was discarded after the 1966 coup.

But the much-ballyhooed “free SHS” scheme may be suffering the same fate as other “flagship” initiatives whose failures are often disguised or misrepresented as unmatched success. Examples include NABCO (crippled with arrears); Planting for Food and Jobs (stalled productivity of about 7.4 metric tonnes per hectare, with notable declines in yam, rice and plantain productivity in 2023); and 1D1F (a 2.5% decline in manufacturing in 2022 and 1.0% in 2023).

Before FSHS in 2017, the Ministry of Education regularly published the Education Management Information System (EMIS) to allow independent analysis of education statistics. Not anymore. EMIS, which is based on the actual number of students reported by secondary schools, is now a tightly guarded state secret. The result is that there are conflicts between the few of its fragmented statistics that do filter out occasionally (after much prying and poking) and statistics from the Computerised School Selection and Placement System (CSSPS), which only reflect students accepted into the various schools, not necessarily those who actually attend them. The latter system, favoured by the government, can overstate the number of students in secondary school.

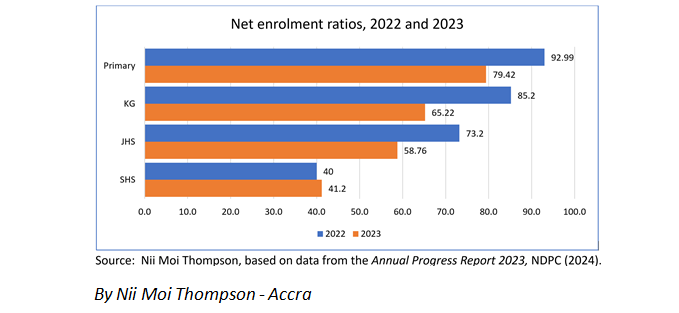

But the 2023 Annual Progress Report (APR) of the National Development Planning Commission (NDPC), which collects and publishes all education (and other) statistics as part of its legal mandate, reveals the true state of free SHS behind the hype (or lies?). The report, published in June 2024, with no fanfare, notes that only 41.2% of children of secondary school-going age were actually in secondary school in 2023, essentially the same as the 40.0% recorded in 2022.

Even more alarming is the fact that the net enrolment ratio for kindergarten – the very foundation of the education system – plunged from 85.2% to 65.2% over the same period, while that of primary school fell from about 93.0% to 79.4%, and JHS from 73.2% in 2022 to 58.8% in 2023. This is a sobering reminder that there is more to a nation’s education system than secondary education, free or not. Focusing on one segment to the neglect of others is a recipe for disaster, which is now the case.

Even then, the completion rate for those who make it to secondary schools has also been in rapid decline, despite government’s deafening claims that FSHS has been a resounding success. The report states: “Completion rate at the SHS level also continued to record a decline to 58.7 percent in 2022/2023 from 68.3 percent in the 2021/2022 academic year. A marginal decline was observed between 2020/2021 academic year (68.6 percent) and that of 2021/2022 academic year.”

And then there’s the question of the actual “free”ness of the programme. A study by Africa Education Watch in 2023 found that parents still bear nearly 80% of the cost that the government claims to have absorbed since 2017. The study also found that the disbursement of budgetary allocations for the programme has fallen steadily from 120% in 2017/2018 to 51% in 2021/2022 (the lowest), resulting in widespread shortages in learning materials and other logistics for secondary schools. Efforts by frustrated and desperate school administrators to address the shortfalls by charging “unapproved fees” have been met with anger and censure by the big wigs at the education ministry.

And so if only 40% of those who should be in secondary school are, and only half of the budget for FSHS is actually disbursed, on what basis does the government claim success so profound that the programme must be enshrined in law? It appears that the government’s efforts to expand and accelerate Mr. Mahama’s “progressively free SHS” programme without much thought or planning have rather done more harm than good to Ghanaian education, government propaganda notwithstanding.

As parliament contemplates legislating “Free SHS”, it must be mindful of its many hidden flaws and failures and address them comprehensively, lest it perpetuates them by law and ruin the future of Ghanaian education.

Public Agenda NewsPaper Ghana's only Advocacy & Development Newspaper

Public Agenda NewsPaper Ghana's only Advocacy & Development Newspaper